I’ve been doing some data-grubbing for textbook revision, and found myself looking at employment data on young (<24) college graduates, which is provided by the BLS in Employment and Earnings. And I came up with a particular number that shows just how devastating the job slump has been and continues to be for the young.

Here’s the question: of college graduates with a bachelor’s degree who aren’t enrolled in further schooling, how many have full-time jobs?

In December 2007, on the eve of recession, the answer was 90 percent.

By December 2009, it was down to 72 percent.

As of December 2010, it had recovered only slightly, to 74 percent.

To me, that’s a tale of young lives blighted, not just in the short run but perhaps permanently: failing to get a job when you get out of school colors your whole career. And it’s still happening.

Yet unemployment has virtually dropped off the political agenda.

Structural Impediment

Interesting and depressing interview with Charles Plosser, the Fed’s reigning inflation hawk. What’s striking is that he is completely committed to the view that we’re experiencing structural employment:

Mr. Plosser’s answer is unequivocal: This mess was caused by over-investment in housing, and bringing down unemployment will be a gradual process. “You can’t change the carpenter into a nurse easily, and you can’t change the mortgage broker into a computer expert in a manufacturing plant very easily. Eventually that stuff will sort itself out. People will be retrained and they’ll find jobs in other industries. But monetary policy can’t retrain people. Monetary policy can’t fix those problems.”

It really makes you despair: we’ve been over and over the evidence, and there’s not a hint in the data that a mismatch between occupations and jobs can explain any important fraction of the jobless rate. But Plosser doesn’t even consider the case that this might not be the story.

Oh, and later he argues that monetary policy should be based on growth rates, not estimates of the output gap; clearly the Fed needed to tighten sharply in 1934:

Eat the Future

The public says it wants to see government spending cut — and the Tea Partiers really, really want spending cut — but people don’t want to cut any program they like; and they like almost everything. What’s a conservative to do?

The obvious answer, once you think about it, is to eat the future: to cut spending in a way that undermines the nation’s long-run prospects, but doesn’t impose all that much pain on voters right now.

And that, as best as I can tell, is the running theme in the cuts proposed by House Republicans. The proposal is, deliberately I think, hard to read and interpret; I hope and assume that the good folks at CBPP will do the detail soon. But on a quick read, here are some of the cuts that jumped out at me:

WIC 1008 million

Food for Peace 544 million

NOAA 450 million

NASA 579 million

Energy efficiency and renewable energy 899

Science 1111 million

Nuclear nonproliferation 648 million

Federal buildings fund 1653 million

Homeland security administration 489 million

FEMA, various, around 1.2 billion

EPA clean water and drinking water about 1.8 billion

Community health centers 1.3 billion

Centers for disease control 900 million

Food for Peace 544 million

NOAA 450 million

NASA 579 million

Energy efficiency and renewable energy 899

Science 1111 million

Nuclear nonproliferation 648 million

Federal buildings fund 1653 million

Homeland security administration 489 million

FEMA, various, around 1.2 billion

EPA clean water and drinking water about 1.8 billion

Community health centers 1.3 billion

Centers for disease control 900 million

WIC is nutritional aid for pregnant women and women with young children; let’s cut that, because the damage to the nation from malnourishment is a problem for future politicians. NOAA is weather and climate — hey, what we don’t know can’t hurt us. Nuclear nonproliferation — well, we probably won’t feel the pain of a terrorist nuke assembled from old Soviet fissile material for a couple of years. FEMA — well, how often do hurricanes hit New Orleans? CDC — with luck, by the time plague hits someone else can be blamed.

Don’t start thinking about tomorrow.

Medicare Recipients Against Handouts

You know, I’d always thought that the “don’t let the government get its hands on Medicare” contingent, while picturesque, wasn’t all that large. But noooo: 44 percent of Social Security recipients, and 40 percent of Medicare recipients, believe that they don’t benefit from any government social program.

Democracy really is the worst system there is, except for all the others.

Is Inflation Baked In?

Whenever I write about inflation or the lack thereof, I get a lot of remarkably angry mail from people who are focused on commodity prices; they just can’t imagine how people like me or Ben Bernanke can be relaxed about the overall inflation picture when the prices of wheat, oil, etc. have risen so much lately.

My usual reply is to point to the distinction between sticky and flexible prices, and argue that it’s the sticky ones we need to worry about. But I’ve realized something else: many of my correspondents don’t seem to realize how little role commodity prices play in overall consumer prices. Not zero: oil prices are a large part of gasoline prices, which are in turn a major expense. But other things we buy, even if they seem to have a large commodity component, are actually made mainly out of labor and other sources of value-added.

Consider, for example, a humble loaf of white bread.

In December, says the Bureau of Labor Statistics, a one-pound loaf cost an average of $1.386. How much of that was the cost of wheat? As best I can tell, a bushel of wheat produces about 63 pounds of bread; wheat has lately been selling at around $10 a bushel; so we’re talking maybe 16 cents of that loaf of bread, or less than 12 percent of the price, reflecting the cost of wheat.

What I get from this is that wholesale food prices have a surprisingly small impact on the price of food, let alone on overall consumer prices. Again, not zero. But it’s not at all peculiar to see large commodity price rises while overall inflation stays low.

Don’t Cut You, Don’t Cut Me

Cut the fellow behind the tree that’s overseas. Pew on public fiscal views isn’t really all that surprising, but it’s still striking: people want spending cut, but are opposed to cuts in anything except foreign aid:

And they want state governments to balance their budgets without cutting spending or raising taxes:

The conclusion is inescapable: Republicans have a mandate to repeal the laws of arithmetic.

Area Illusion

I’m a big fan of Gillian Tett’s work, but — such statements always come with a “but”, right? — in today’s piece she falls prey to a map trick. She looks at the divergence in unemployment rates among US states, and suggests that America is experiencing European-style divergence:

In the last few months, there has been a flurry of hand-wringing about the high level of US unemployment, currently running at about 9 per cent. But what is equally striking is the variation between regions: while some places such as North and South Dakota, or Nebraska, had rates below 5 per cent in December 2010, Florida, California and Nevada all posted rates above 10 per cent.

And it’s true that if you look at a map, it seems as if there are large regions with low unemployment:

But nobody lives there: the Dakotas and Nebraska combined have only 3.3 million people, around 1 percent of the US total.

What you really want to do is compare large US states with large European nations. And there aren’t any low-unemployment large states. Yes, there’s a divergence: New York and Texas have unemployment rates of 8.2 and 8.3 percent, respectively, while California’s rate is 12.5. But that’s nothing like the divergence between Germany, with a 6.6 rate, and Spain, with a 20.2 rate.

For the most part, all of America is sharing in this slump.

Johnny Reb Economics

Mike Konczal has a post about Ron Paul’s first hearing on monetary policy, in which he points out that the lead witness is a big Lincoln-hater and defender of the Southern secession.

And it’s true! I went to his articles at Mises, and clicked more or less idly on the piece about American health care fascialism — I guess that’s supposed to be a milder term than fascism, although he seems to equate the two. And sure enough, he ends:

This is not likely to happen in the United States, which at the moment seems hell-bent on descending into the abyss of socialism. Once some states begin seceding from the new American fascialistic state, however, there will be opportunities to restore healthcare freedom within them.

I presume that Amity Shlaes is already working on her Lincoln assessment, The Even More Forgotten Man.

Gimme an A! Gimme an E! Gimme an R!

The American Economic Review is celebrating its 100th anniversary with aspecial issue commemorating the top 20 papers of the past century. You can read the survey article here (pdf); free links to the papers are included in the survey.

Big props to Peter Diamond, who gets two entries. Some other people you may have heard of also made the list.

Update: As several people pointed out, Joe Stiglitz also has two entries. No surprise — as I’ve said before, Joe is an insanely great economist. It’s also worth noting that a number of the papers on the list involve very simple, intuitive models — that includes Friedman on the natural rate, Krueger on rent-seeking, Mundell on currency areas; Shiller’s great piece on stock volatility was also a remarkably simple concept yielding a powerful insight. My own paper was actually pretty math-heavy; uncharacteristically, it’s also a paper in which doing the math fundamentally changed my mind about things (I didn’t believe the home market effect was real until it popped out of the equations; only then did I realize it was obvious.)

I’m not sure why there weren’t more post-1980 papers; it might just be that it takes several decades before everyone agrees that a paper was great.

Why Expectations Matter

Paul Segal has a good post over at the FT about inflation expectations, and in particular about what the UK should do in the face of a recent rise in headline inflation:

Hawkish discussions of inflation expectations today, and their potential effects on actual inflation in the future, remember the conclusion but seem to have forgotten the argument. Expectations of high future inflation lead to high actual inflation in the future only if workers and firms are able to pass that expected price rise through to their own contracts.

Indeed. As I’ve tried to explain in the past, what we need to worry about is a sort of leapfrogging process that perpetuates inflation once it has gotten embedded in the economy:

Suppose that I’m setting my price for the next year, and that I expect the overall level of prices — including things like the average price of competing goods — to rise 10 percent over the course of the year. Then I’m probably going to set my price about 5 percent higher than I would if I were only taking current conditions into account.And that’s not the whole story: because temporarily fixed prices are only revised at intervals, their resets often involve catchup. Again, suppose that I set my prices once a year, and there’s an overall inflation rate of 10 percent. Then at the time I reset my prices, they’ll probably be about 5 percent lower than they “should” be; add that effect to the anticipation of future inflation, and I’ll probably mark up my price by 10 percent — even if supply and demand are more or less balanced right now.Now imagine an economy in which everyone is doing this. What this tells us is that inflation tends to be self-perpetuating, unless there’s a big excess of either supply or demand. In particular, once expectations of, say, persistent 10 percent inflation have become “embedded” in the economy, it will take a major period of slack — years of high unemployment — to get that rate down.

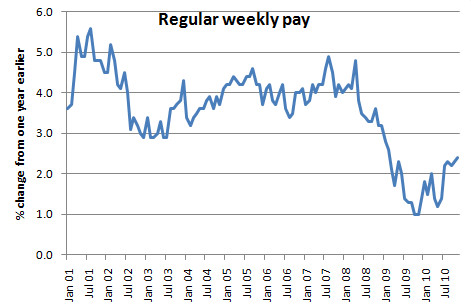

The key thing in the British case is that there’s no sign that anything like that is happening. Headline inflation is up because of food, energy, depreciation of the pound, and increases in VAT; but sticky-price leapfrogging isn’t evident at all. Here’s regular weekly pay:

Think of it this way: to raise rates in the UK now would be to demand that wage growth, already far below recent norms, slow further. That’s not a sensible policy in response to a one-time bulge in headline prices.

Ideas Are Not The Same As Race

Every once in a while you get stories like this one, about theunderrepresentation of conservatives in academics, that treat ideological divides as being somehow equivalent to racial differences. This is a really, really bad analogy.

And it’s not just the fact that you can choose your ideology, but not your race. Ideologies have a real effect on overall life outlook, which has a direct impact on job choices. Military officers are much more conservative than the population at large; so? (And funny how you don’t see opinion pieces screaming “bias” and demanding an effort to redress the imbalance.)

It’s particularly troubling to apply some test of equal representation when you’re looking at academics who do research on the very subjects that define the political divide. Biologists, physicists, and chemists are all predominantly liberal; does this reflect discrimination, or the tendency of people who actually know science to reject a political tendency that denies climate change and is broadly hostile to the theory of evolution?

Now, I don’t mean to say that political bias in the academy is absent, although it’s not consistent: I can well imagine that it’s hard to be a conservative in some social sciences, but in economics, the obvious bias in things like acceptance of papers at major journals is towards, not against, a doctrinaire free-market view. But the point is that doing head counts is a terrible way to assess that bias.

Speaking of Extreme Weather

Urp:

The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization issued an alert Tuesday that a severe drought was threatening the wheat crop in China, the world’s largest wheat producer, and was even resulting in shortages of drinking water for people and livestock.The state-run news media in China warned Monday that the country’s major agricultural regions were facing their worst drought in 60 years and said Tuesday that Shandong Province, a cornerstone of Chinese grain production, was bracing for its worst drought in 200 years unless substantial precipitation came by the end of this month.

By the way, the article says that China is largely self-sufficient in grains, which is true. But in recent years China has become a huge importer of soybeans, which compete for land and other resources with grain production; that’s how Chinese growth puts pressure on world food prices. If China has to import wheat, too, that’s seriously ungood.

Supply and Demand and QWERTY

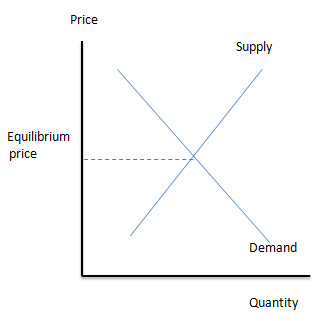

A number of readers seem to think that I’ve mislabeled the axes on this figure:

Um, no. That’s your basic Econ 101 graph.

The problem you may have is that for reason not worth going into, economics long ago settled into the habit, in this case, of putting the independent variable on the wrong axis. The supply curve shows how much producers are willing to supply for any given price. The demand curve shows how much consumers want to buy for any given price. The equilibrium price is the one that matches the quantity supplied to the quantity demanded.

Why not switch axes? It’s a QWERTY problem: everyone has been drawing the diagram this way for more than a century, so that anyone trying to put out a textbook that did it the other way would lose a lot of potential adoptions from professors who don’t want to change their notes.

So, no error there, just a long and strange tradition.

Gradual Trends and Extreme Events

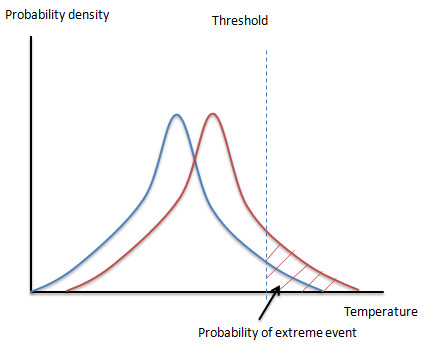

I’ve spent a lot of the last several days reading about climate change, extreme weather events, food prices, and so on. And one thing that became clear to me is that there’s widespread misunderstanding of the relationship between the gradual trend of rising temperatures and the extreme weather events that have become so much more common. What I’m about to say may seem obvious, because it is obvious, at least if you approach it the right way; but I still think it needs saying.

So, let’s start with an observation: weather varies. (Duh.) Heat waves and other stuff happens. Think of it in terms of a probability distribution for temperatures, with the area under the curve over some range representing the probability of temperatures in that range in a given place over a given period. And define an extreme event as a case in which the temperature exceeds some threshold. The the picture looks like this:

Now suppose that a warming trend shifts the whole probability distribution to the right — which is what we mean when we talk about climate change. Then the result looks like this:

What happens is that the right tail gets fatter: the probability, and hence the frequency, of extreme events goes up.

Two immediate implications. First, there will still be cold stretches: global warming shifts the distribution, it doesn’t eliminate the left side of the distribution. So there will still be cold spells; that proves nothing.

Second, no individual weather event can properly be said to have been “caused” by global warming. Heat waves happened 30 years ago; there’s no way to prove that any individual heat wave now might not have happened even if we hadn’t emitted all that CO2.

But the pattern should have changed: we should be getting lots of record highs, and not as many record lows — which is exactly what we do see. And we should be seeing 100-year heat waves and similar events much more often than history would have suggested likely; again, that’s what we actually do see.

The point is that the usual casual denier arguments — it’s cold outside; you can’t prove that climate change did it — miss the point. What you’re looking for is a pattern. And that pattern is obvious.

Slow Food

Update: Link fixed

Now that I’m doing more reading about food markets, I’m spotting interesting items that I would have missed. Here’s one:http://www.agrimoney.com/news/heathrow-chaos-turns-lonrho-to-sea-freight–2784.html:

The vulnerability of Heathrow airport to snow has prompted Lonrho to turn from airplanes to ships to ensure its Africa-grown produce is delivered to European retail giants such as Marks & Spencer and Tesco.The John Deere retailer-to-hotels conglomerate said that its Rollex business had lost £700,000 in turnover to December’s chaos at the London air traffic hub, which was closed by snow for four consecutive days.To “mitigate future risk”, Rollex, which from its base in South Africa exports fruits and vegetables from throughout the continent, had approached shippers to guarantee deliveries to its European buyers, which also include the likes of Sainsbury, TFC Holland and Univeg.The initiative, which Lonrho described as a “back-up” to airfreight, had been enabled by refrigeration advances, and comes amid growing unease among European consumers at the environmental costs of flying in foodstuffs.