Metro Detroit no longer most segregated

Mike Wilkinson, Detroit News staff writer

The steady movement of African-Americans from Detroit to area suburbs helped knock the region off the top of the list of most-segregated regions in the country.

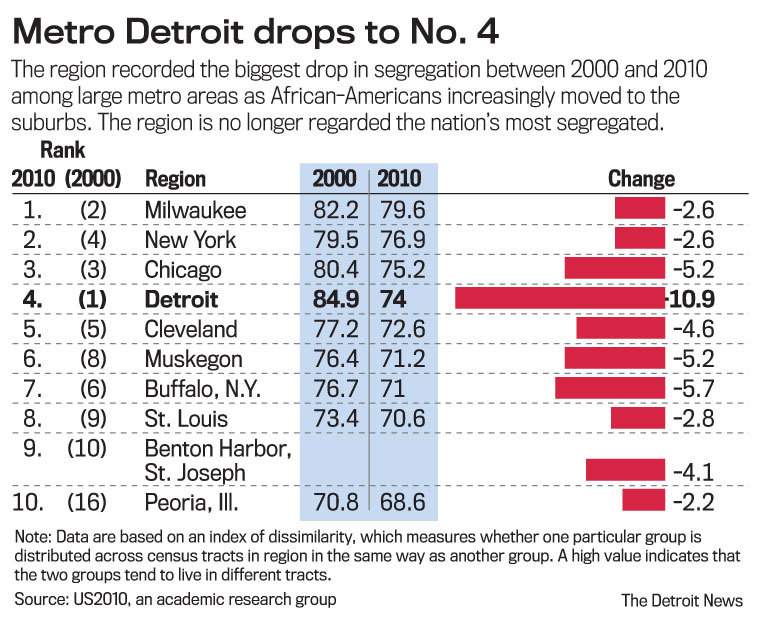

Metro Detroit is now No. 4, behind Milwaukee, New York and Chicago, respectively, based on a statistical analysis of census data released last week.

And although the region remains highly segregated, it experienced the biggest drop in a nationally recognized segregation index, with nearly twice as many people now living in areas that are considered integrated, compared with just 10 years ago. The changes are a byproduct of migration patterns that have dramatically altered communities throughout Macomb, Oakland and Wayne counties.

"It deserves a lot of recognition," said John Logan, a sociologist at Brown University who compiled the statistics for the US2010 research project. "A lot had to change on the ground for the number to change so much."

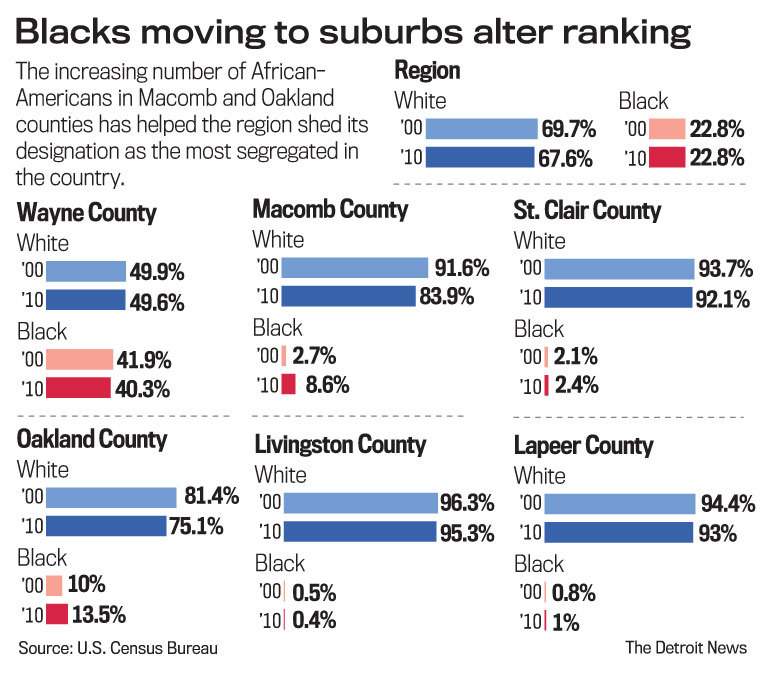

Segregation is measured by looking at the racial balance in a region and seeing the comparison to neighborhoods — defined by census tracts of roughly 4,000 people. In the Detroit area, the region comprises Wayne, Oakland, Macomb, St. Clair, Lapeer and Monroe counties.

In 2000, more than 100 census tracts in the Metro area had a black population of between 12 and 50 percent, a rough indication of integration. In 2010, that number had jumped to 204 tracts — with 694,484 people living in those types of tracts, up from 349,453 in 2000.

Although the black population held steady at about 22 percent in the region between 2000 and 2010, its composition within it changed dramatically, prompting the substantial dip in segregation.

Segregation and its related costs have struck almost all parts of the region. The impact often is obvious, yet other times subtle.

For residents in far-off suburbs, it can mean long commutes, higher mortgage costs and sometimes minor irritants like lower water pressure. For urban residents, it can be high crime, dilapidated housing and poor access to quality education, jobs and good health care.

For those who have helped change the complexion of the suburbs, the reasons they moved out of Detroit was rooted in something simple and enduring: a better life.

"Sometimes the answer with having a better quality of life means moving north," said Gwen Thomas, who moved to West Bloomfield from Detroit 11 years ago. "For a long time, people were dedicated to staying in Detroit. We love Detroit, but at some point, they wanted a better quality of life, and they just got tired of the challenges in Detroit — city services, which include the school district, crime, higher taxes. You begin to weigh what's more important."

'Index of dissimilarity'

With the release of data that completes the census rollout, researchers were able to compile an "index of dissimilarity" for every region in the country. It measures whether blacks and whites are distributed equally across a metropolitan area.

Based on the calculations, Detroit posted a 74, down substantially from the 84.9 score registered in 2000 and well below its 87.6 score in 1990. Anything above a 60 is considered a very high level of segregation . A "60" indicates that 60 percent of one group would have to change neighborhoods to get a distribution more in line with the region's white-black composition, which stands at 67.6 percent white and 22.8 percent black.

Considered alone, however, Wayne County would remain the most segregated place in the United States, according to Logan's research. That's a result of Detroit's highly segregated census tracts, where only a fraction of the tracts aren't majority black, and the predominantly white suburbs like Livonia and Wyandotte. But others in the county did change markedly, like Westland, whose black population jumped from 6.7 percent to 17 percent.

Some large regions with high segregation, like New York and Chicago, comprise portions of as many as three states and dozens of counties. In those much larger regions, as you get farther from the urban center, segregation increases as the minority population typically declines markedly.

Big-city diversity

New York and Chicago are far more diverse than Detroit, with white populations of 48.6 and 55 percent, respectively. Hispanics make up a fifth of both metros, and blacks about 17 percent. But in many areas of the two, segregation persists; in Manhattan, for instance, large swaths of the Upper East Side and Midtown have neighborhoods where more than 80 percent of the residents are white and where less than 10 percent are black or Hispanic.

Yet in Queens, many tracts are more than 80 percent Hispanic; in Brooklyn, blacks make up a majority of dozens of census tracts and in dozens more whites exceed 80 percent. In the far eastern end of Long Island, whites comprise more than 70 percent of the population.

In Chicago, the differences are just as stark. The suburban counties are predominantly white, while Cook County is just 44 percent white. But even in the city, one street can act like Eight Mile does in Detroit: In the western part of Chicago, one census tract of 4,530 was 95 percent black in 2010; the tract just west of it, with 3,934, is 89 percent Hispanic.

Locally, the biggest demographic changes took place in Macomb County, where the number of African-Americans more than tripled to 72,053. Another 42,595 moved to Oakland County.

Wayne County lost 131,826 African-Americans, according to the latest census numbers. All three counties lost white population; many of them were believed to be part of the flight to other states as part of the massive movement out of Michigan during the height of the recession.

Some tensions raised

Despite the improvements in the racial balance of the region, the increasing diversity has raised tensions in some communities and schools.

Kurt Metzger, a Detroit demographer, is hopeful those tensions won't generate another wave of white flight. He would like people to see that the diversity surrounding them is part of a national, not just local, trend. Almost every region of the country saw segregation decline, though none as fast as Detroit.

"It really is important that people understand the changes demographically of their county, their neighborhood, their community … to some degree reflects what's happening nationally," Metzger said.

"I think there's much to be said for not being afraid of these (changes)."

Thomas, a native Detroiter and president of the southern Oakland County branch of the NAACP, said she is pleased to see an influx of African-Americans and is as hopeful as Metzger.

"Our neighbors begin to see how important diversity is at home and at work," Thomas said. "We learn how to respect each other. It's not all 'kumbaya,' but we're getting there."